Visible War / Invisible War

Ars Longa & Berg Contemporary 2025

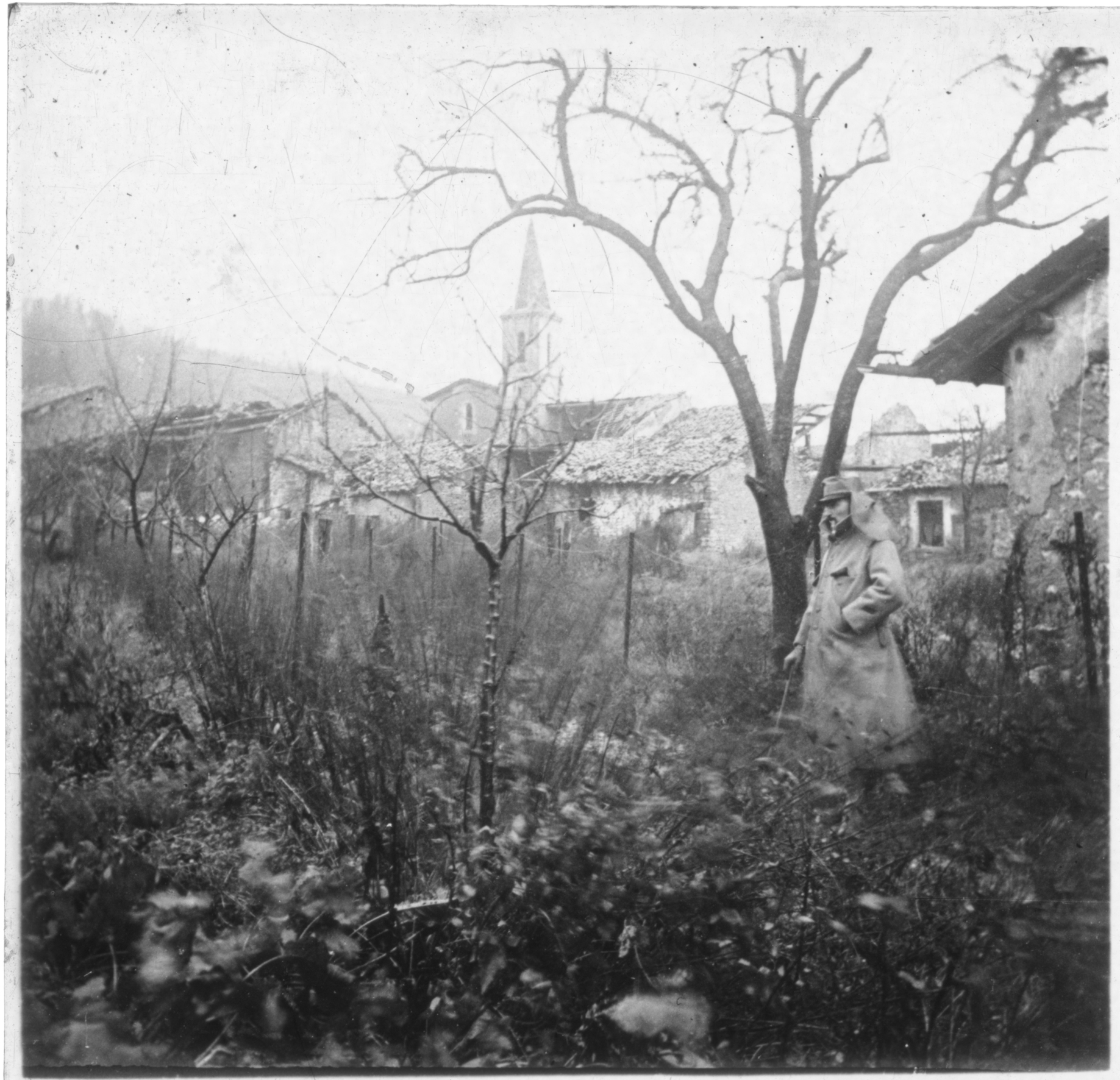

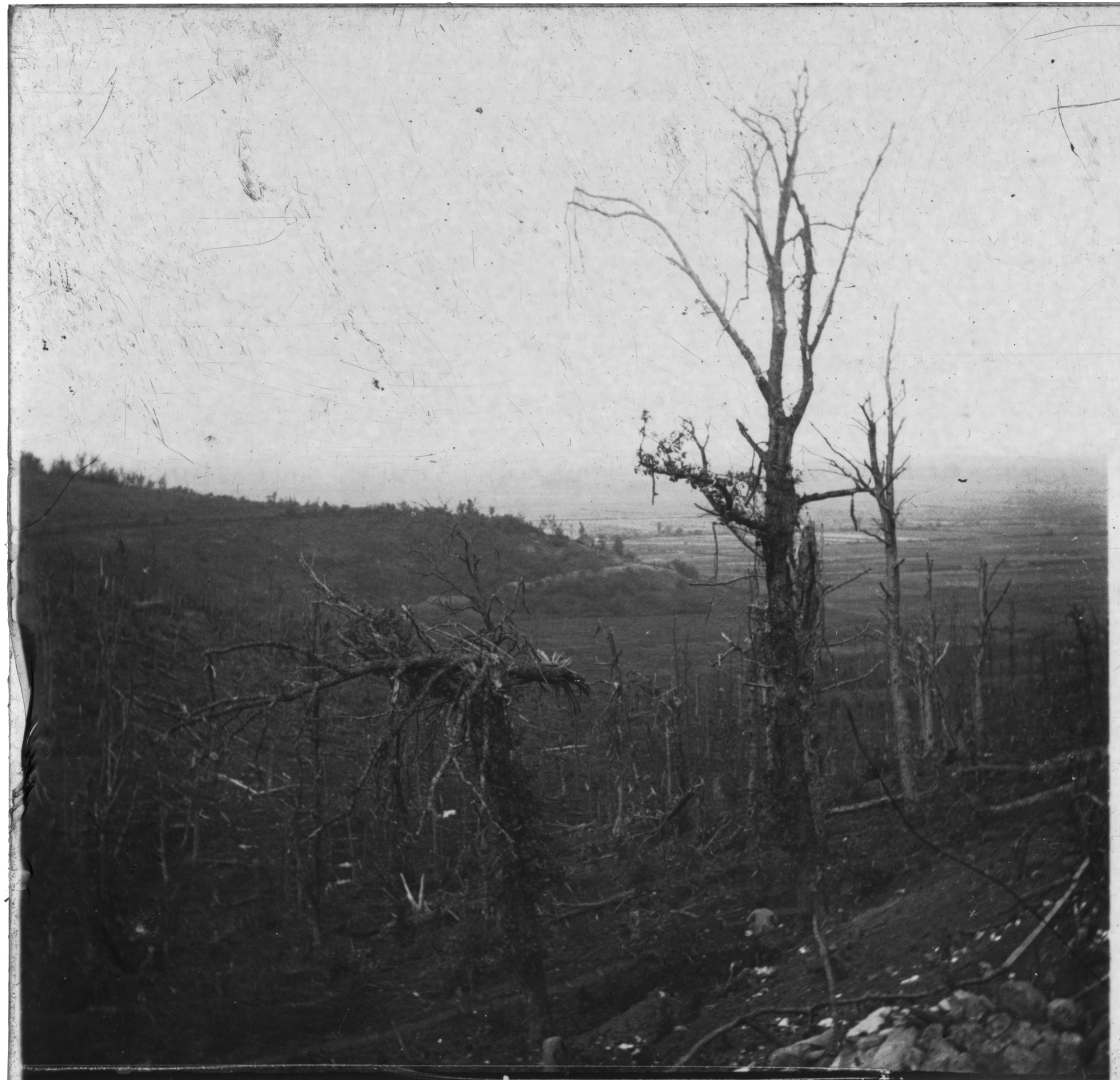

“Hallgerður Hallgrímsdóttir’s photographic diptych, Invisible War (documentation of the community gardens of Suomenlinna fortress) and Visible War (documentation of technological developments in the respective fields of photography and military conflict), draws together two temporal landscape of conflict: the hushed, silver-toned glass plate images taken on the battlefields of the First World War, and vivid color photographs on silk of late-summer vegetation on Suomenlinna, a historic fortress islan off the coast of Helsinki. Across these two series—one found, one made—Hallgrímsdóttir traces an affective ecology of aftermath and environmental trauma, where soil holds the sediment of violence and plants rise, cautiously, through contaminated ground. Here, affective ecology is not simply about harmony with nature but about living with the emotional weight of damaged landscapes. It is about how we register harm through the senses—through soil that can’t be touched, flowers that bloom despite and images that offer space to feel what language cannot hold.”

- Becky Forsythe and Þórhildur Tinna Sigurðardóttir, from the exhibition catalogue for In the Undergrowth.

In the Undergrowth / Í lággróðrinum - Ars Longa, Djúpivogur

Ósýnilegt stríð / Sýnilegt stríð

Ars Longa & Berg Contemporary 2025

„Tvíþætt ljósmyndasería Hallgerðar Hallgrímsdóttur, Ósýnilegt stríð (skrásetning á samfélagsgörðum Suomenlinna-virkis) og Sýnilegt stríð (skrásetning á tækniframförum á sviði ljósmyndunar og hernaðar), tengir saman landslag átaka frá ólíkum tímum: lágstemmdar glerplötumyndir með silfurblæ, teknar á vígvöllum fyrri heimstyrjaldar, og litsterkar myndir af síðsumarsgróðri á eyjunni Suomenlinna rétt utan við Helsinki. Með þessum tveimur myndaröðum sínum - önnur er fundin, hin tekin af listakonunni sjálfri – teiknar Hallgerður upp tilfinningalegt vistkerfi eftir umhverfisáfall, þar sem moldin ber í sér dreggjar ofbeldis og gróðurinn rís varfærnislega upp úr mengaðri jörðu. Hér snýst tilfinningaleg vistfræði ekki aðeins um að finna samhljóm með náttúrunni heldur um að lifa með þeim þyngslum sem fylgja landslagi þar sem stríð hafa verið háð. Hún snýst um það hvernig við meðtökum slíkan skaða með skilningarvitunum – í gegnum mold sem ekki má snerta, blóm sem blómstra þrátt fyrir allt, og myndir sem bjóða okkur að finna fyrir því sem tungumálinu er um megn að fanga.“

- Becky Forsythe og Þórhildur Tinna Sigurðardóttir, úr sýningarskrá fyrir Í lággróðrinum.

Bystander / Sjónarvottur - Berg Contemporary, Reykjavík